March 6, 2024

GDI's Top Trends of 2024

As we enter 2024, cleaning up our polluted online information environment has become increasingly complex and urgent. The spread of harmful, hostile narratives poses a growing threat to democracy, public health and social cohesion. New technologies and tactics are emerging daily, making disseminating disinformation cheaper and easier than ever before. Some global leaders are pushing ahead with transformative digital policy solutions, but some experts worry that the technology far outpaces the world’s ability to regulate.

With major European Union and US elections in the latter half of the year, all eyes are on experts to help global leaders unpack how disinformation will affect civic integrity - and hopefully prevent it. Right now, that prognosis seems fairly bleak, but there are a few reasons for hope.

A confluence of trends in the private sector, governance and civil society are driving the issue. At the same time that AI-generated tools like deepfakes have started wreaking political havoc on both sides of the Atlantic, major tech platforms have been slashing trust and safety teams and squeezing researchers out of data access. While the EU is taking a major stride towards tech regulation through the new Digital Services Act, the US - where most major tech companies are based - is woefully behind on basic privacy and children’s safety regulation. Furthermore, a massive backlash against counter-disinformation work in several countries is constraining research and leaving tech companies and governments without sufficient help - or critical external perspective - to safeguard their election systems.

All of these factors combined create a challenging environment for the counter-disinformation community to reinforce civic integrity at a moment where that task has never been more critical. There is reason, however, to be optimistic. Several countries are making significant progress on children’s online safety legislation, which could be the tip of the spear for more widespread, common-sense tech regulation. As the EU forges ahead on DSA enforcement, the landmark legislation could serve as a model for other legislative bodies. Additionally, the backlash against counter-disinformation work may have the opposite effect, shining a spotlight on an area that needs the world’s attention and proving the important impact of the work.

The battle against disinformation is constantly evolving to meet this rapid pace of change. GDI is always adapting our tools, frameworks and methods to build an engine capable of identifying even the most subtle of disinformation narratives as they spread across the internet. Building this engine requires a mix of data science, intelligence analysis and policy research. This multi-front effort gives us a unique perspective on the most pressing disinformation challenges we will face in 2024.

Data Science

If last year was the year of ChatGPT, then 2024 may be the year of the great LLM-induced search engine meltdown.

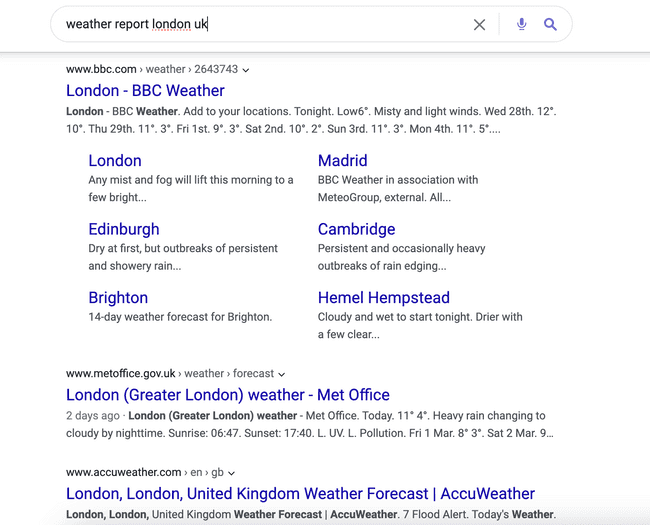

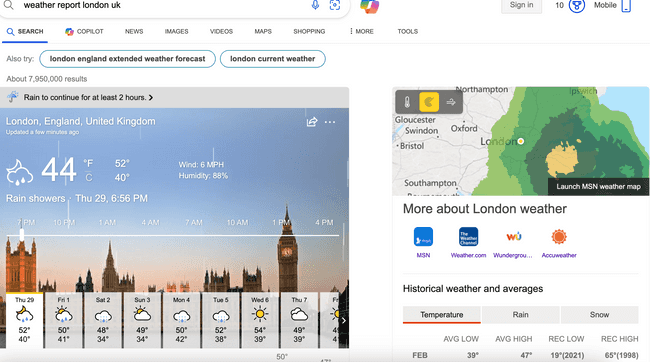

Prior to the release of popular large language models (LLMs) like OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Gemini (formerly Bard) or Anthropic’s Claude, search engine results were fairly straightforward. A Google, Bing or DuckDuckGo user could expect to see several pages of indexed web content relevant to their query. Until about 2022, it was generally assumed that humans wrote the content that appears in those search results and that humans trained the algorithms that index that context. Additionally, until recently, search results would present direct links instead of LLM-generated responses to a search query. For example, when searching for the weather report in previous years, you would get a list of relevant websites – your local news, national weather services and so on. Nowadays, you’ll likely see an LLM-generated summary of the top results before you see any links to an original source.

An example of this is below. The top image shows a basic search result for the weather, and the bottom image shows an LLM-generated search result summary.

As LLMs are increasingly integrated into major search engines, these previous assumptions can no longer be taken for granted - and opens the most popular way to browse the internet to a tidal wave of disinformation risk.

Though much attention has been devoted to LLMs’ ability to produce convincing, completely fabricated information and subsequent societal consequences, their harmful potential on search results needs some spotlight. Using LLMs to analyse, aggregate and present modified search results could wrongfully prioritise false or misleading but seemingly trustworthy information. The sharp proliferation of AI-generated spam content heightens this risk. LLMs summarising AI-generated disinforming content in its search engine result summary could produce a snake-eating-its-own-tail effect; an explosion of AI-generated spam sites hits the web, moves up in search engine results, and then LLMs are deployed to summarise those top search engine results to a user, who has no idea that they are reading disinformation. In this scenario, search engines would have to deal with a runaway disinformation problem that renders search results essentially useless.

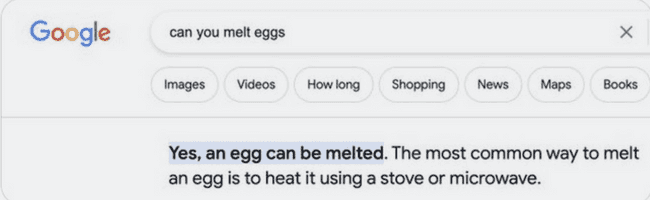

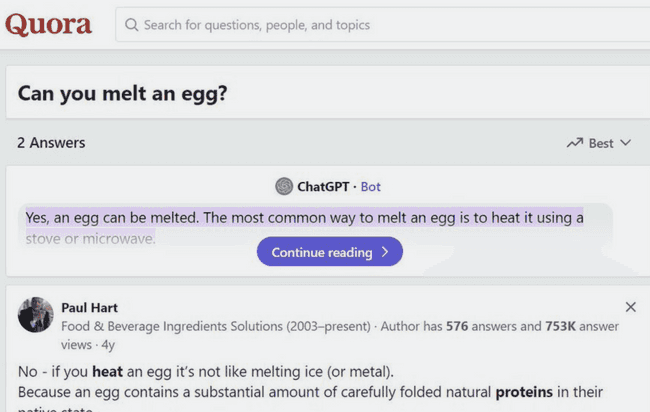

In September, Ars Technica published a piece on an example of the snake-eating-its-own-tail effect in action - a simple search for “can you melt eggs?” on Google. Google’s LLM search summary pulled its top answer from Quora, which, in turn, pulled its top result from ChatGPT. All of them erroneously stated that you can melt eggs, seen in the screenshots below.

The top image shows a screenshot of an LLM-generated search summary from Google providing false information, and the bottom image shows ascreenshot of the top answers to a Quora search query with the top result delivering false information from ChatGPT. Google used this for its erroneous search engine summary.

GDI believes that detecting harmful content across languages and geographies in real time could halt search engines’ slide down a slippery slope. By identifying and marking disinforming content as quickly and accurately as possible, the likelihood of that content being fed to the LLM and regurgitated back through the information system all the way to a user is drastically reduced.

Intelligence Analysis

In a major election year, GDI’s intelligence analysts are focusing a great deal on civic integrity. Pillars of trust and legitimacy uphold the credibility of democratic elections. However, this foundation of modern democracies is under assault by the insidious promotion of disinformation crafted to undermine public confidence and manipulate electoral outcomes. Beyond the more obvious unfounded claims of meddling in electoral processes and results, a spectrum of issues ranging from global conspiracies and international conflict to pseudoscience and bigotry are weaponised to sow discord, erode trust and ultimately subvert the democratic will of the people.

Impactful adversarial narratives include global conspiracies, various representational harms (racism, anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment, misogyny, and other forms of bigotry), and environmental and health pseudoscience. These narratives intersect and amplify one another, resulting in compounded harm. Global conspiracies serve as potent fuel for efforts to undermine public faith in functioning democracies and delegitimise electoral outcomes, alleging widespread rigging and secret plots. Pseudoscience narratives, often intertwined with political agendas, are leveraged to promote mistrust in scientific consensus and are commonly deployed to prevent government action on climate change or public health. Representational harm-related narratives are used to alienate, intimidate and suppress the political participation of marginalised communities and can lead to real-world violence.

Though disinformation originates from many sources, much of the world’s attention is on the impact of Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) on key elections. State and state-aligned actors may seek to widen domestic cleavages, undercut faith in electoral processes, support a specific candidate or merely muddy the information landscape to sow discord. FIMI actors weaponise all of the above narratives to these ends and are aided by increasingly sophisticated technology.

While the world focuses on the latest tech and emerging capacities to spread disinformation, there is a risk of ignoring the kind of “low-tech” manipulation and interference that states have always used: coordinated disinformation amplification via tried and tested channels of communication on the open web and social media, as well as through the use of domestic actors to launder adversarial narratives. Such tactics have existed far longer than deepfakes and related AI-augmented manipulations. GDI believes these low-tech tactics may be equally or increasingly effective this year even as generative AI steals the spotlight.

Policy

2024 marks the year the European Union’s landmark tech legislation, the Digital Services Act, enters into force. The DSA, alongside related laws such as the Digital Markets Act and the Code of Conduct on Disinformation, could be the world’s model for transformative tech regulation - or it could collapse under the weight of legal gaps and compliance issues.

One key aspect under scrutiny is the extent to which these laws will address programmatic advertising, particularly the ability of ad-tech companies to circumvent Very Large Online Platforms (VLOP) requirements concerning data sharing under the DSA. Meanwhile, the availability of funding for independent civil society by the European Union to support third-party scrutiny of ad tech transparency is critical to understanding ad tech’s compliance and behaviour in the new regulatory landscape. Depending on the effectiveness of these initiatives and the outcome of upcoming EU elections, a demand may emerge for an EU Programmatic Advertising Act directly tackling issues within programmatic ad tech. These issues include ensuring transparency in ad placement pipelines, comprehensive policy formulation and enforcement mechanisms, and investment in trust and safety teams.

The US landscape is marked by the potential for significant policy shifts, tempered by legislative gridlock and upcoming elections. The US government has recently begun to show an appetite for a more assertive regulatory approach towards the tech industry. This could manifest through actions such as enforcing antitrust mandates by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which is currently examining relevant matters like Microsoft's investment in OpenAI and Adobe's attempted acquisition of Figma. Moreover, despite legislative turmoil in Congress, some pieces of legislation, like the Kids Online Safety Act, have started to gain bipartisan traction. Although the US may presently lag behind the EU, the potential for swift action still exists if political will catches up.