July 13, 2023

How Disinformation Is Undermining Our Human Rights

Over the past century, the world has focused on defining and securing human rights for all. In 2022, the Human Rights Council affirmed in resolution 49/21 that “disinformation can negatively affect the implementation and realisation of all human rights.” Though disinformation has always existed, the digital revolution has allowed it to spread farther and faster around the globe. Meanwhile, advertising technology has enabled the monetisation of harmful content, and as harmful content is often engaging, this has created an economic incentive to peddle disinformation. To avoid unravelling the progress we have already made and ensure human rights for the generations to come, it’s critical for countries around the world to take the threat of disinformation seriously.

Data shows that disinformation is significantly undermining human rights all over the world by disrupting civic integrity, eroding faith in public institutions and inflaming social hatred. The UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression reiterated the need to build social resilience against disinformation and promote multi-stakeholder approaches that engage civil society as well as states, companies and international organisations.

GDI aims to contribute to building social resilience and protecting information integrity by increasing transparency around monetisation of content, therefore supporting responsible choices to disincentivise the creation and spread of online disinformation.

We view disinformation through the lens of adversarial narrative conflict which exacerbates socio-cultural divisions, fuels anger among individuals and seeks to uproot trust in democratic institutions. Our definition of disinformation is grounded in and informed by internationally recognised human rights standards, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Examples of adversarial narratives undermining some of our most basic human rights are, unfortunately, not difficult to find. Below are just a few examples of how disinformation impacts civic integrity, trust in institutions and sows hatred.

Democracy and Civic Integrity

The right to free and fair elections has been mandated by the United Nations as a human right since 1976. The UN Human Rights Committee has also asserted that states and their governments are required to ensure that voters are free from interference and can form their own opinions independently. For this to take place, voters must have access to trustworthy and reliable sources of information regarding candidates and where, when and how to vote. The production and circulation of disinformation from both governments and individuals online can, and has, stopped such free and fair elections from taking place.

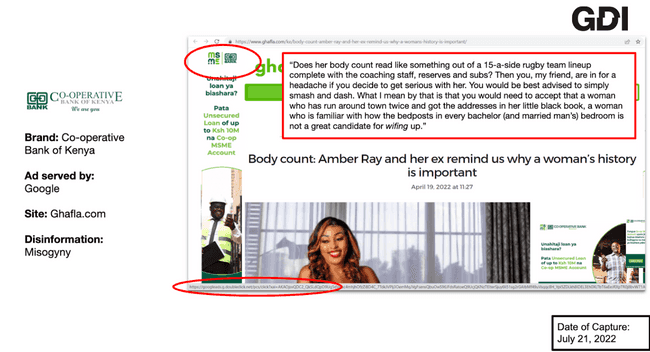

During Kenya’s 2022 General Election disinformation was used to undermine women’s capacity to make informed political decisions. It also undermined their roles in public institutions, including running for political office. The spread of these narratives on platforms such as TikTok and the open web inflamed political tensions, which stoked fears of election-related violence. This attempt to dissuade women from running for office and participating in the electoral process has disturbing effects on civic integrity and lays the ground to exclude women from the basic right to self-governance. Below is just one example of this phenomenon.

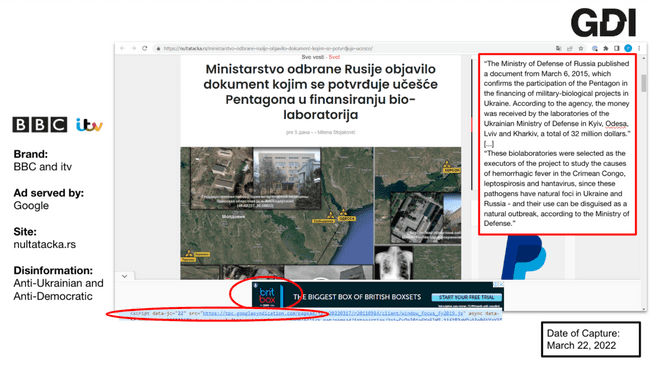

It has also been seen in major atrocities such as the Rwandan genocide and more recently, during the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Such examples of anti-Ukrainian narratives have been extensively tracked by GDI since the outbreak of the conflict, with just one example of this below.

Which human rights are impacted by democracy and civic integrity disinformation?

- The UN strongly supports democratic governance, namely a set of values and principles that support greater participation, equality, security and human development as embodied in the UN Charter, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and other core international human rights law conventions and standards. Therefore, threats to democratic governance and international order risks and undermines these rights.

- A democratic and equitable international order fosters the full realisation of all human rights for all, and everyone is entitled to it (see UN Human Rights Council, HRC, Resolution 18/6, 33/3, 36/4, 39/4, 42/8, 45/4, 48/8 ,75/178).

- Democratic and equitable international order means that all peoples have:

- Rights to peace, international solidarity, development and self-determination.

- Right to exercise effective sovereignty over their natural wealth and resources.

- Right to freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.

- Right to have equal opportunity to participate meaningfully in regional and international decision-making.

- Right to have a shared responsibility to address threats to international peace and security.

- Other requirements include:

- Promotion and consolidation of transparent, democratic, just and accountable international institutions in all areas of cooperation.

- Promotion of a free, just, effective and balanced international information and communications order.

- Full respect for sovereignty, territorial integrity, political independence, the non-use of force or the threat of Force in international relations and nonintervention in matters that are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any State.

- Art 21 (3) Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR); art 25(b) ICCPR; art 5(c) International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD); art 7 Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).

- Right to take part in the government of your country, directly or through freely chosen representatives- art 21(1) UDHR, art 25(a) ICCPR, art 5 ICERD, art 7 CEDAW.

- Right to equal access to public service in your country- art 21(2) UDHR, art 25(c) ICCPR, art 5 ICERD, art 7 CEDAW

- Right to vote shall be subject to only reasonable restrictions such as age limit others such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth, disability or other status constitute discrimination.

- Right to equality and non-discrimination art 2(2) and art 3 of ICESCR; art 3 and 26 of ICCPR; art 2 ICERD, art 1, 2 and 8 CEDAW etc.

Prerequisite rights to enable an environment for free and genuine elections:

- Freedom of opinion and expression and to access information- art 19 ICCPR.

- Voters should be able to form opinions independently, free of violence or threat of violence, compulsion, inducement or manipulative interference of any kind (para 19 CCPR 25 of 1996).

- Freedom of peaceful assembly- art 21 ICCPR.

- Freedom of association- art 22 ICCPR.

- Freedom of movement- art 12 ICCPR.

- Right to education- art 13 and 14 ICESCR.

- Right to life - art 6(1) ICCPR.

- Right to liberty and security of person- art 9(1) ICCPR.

Trust in Science

Disinformation polarises communities and societies by feeding audiences with divisive and misleading content that obscures, contradicts and undermines scientific, fact-based information critical to public health and safety. Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services.” When disinformation destabilises public trust in institutions, these human rights are threatened. During the COVID-19 pandemic, a rise in pseudo or anti-science disinformation undermined informed and accurate decision making around personal and community health.

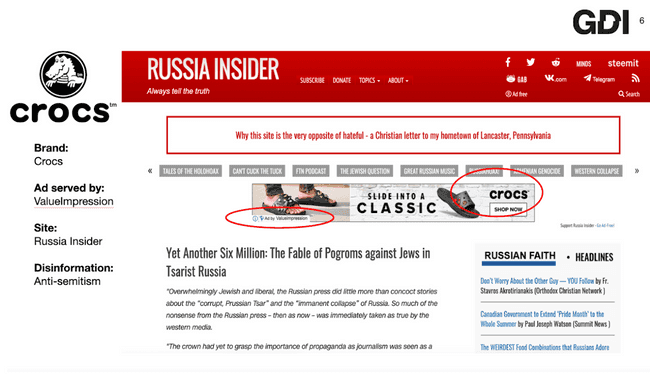

‘The Great Reset’ is a prolific disinforming narrative that emerged from the pandemic with roots in anti-semitism and conspiratorial claims of a new world order controlled by global elites. Specifically, the Great Reset claims that COVID-19 and/or the vaccine was purposefully introduced as a population control plan implemented to help the global elite consolidate their power. GDI has found examples of monetised articles that promote this theory and weaken trust in scientific fact.

Which human rights are impacted by anti-science disinformation?

- Right to highest attainable standard of mental and physical health

- art 12 of ICESCR .

- art 24(1) of CRC on children.

- people with disabilities art 25 CRPD on people with disabilities.

- principle 11 Resolution 46/91 on elderly persons.

- art 10(h), 11(f), 12(1) and 14 (2)(b) CEDAW on women.

- art 5(d)(iv) ICERD on race, colour, ethnicity or nationality.

- art 25(1)(a), 28, 43(1)(e), 45(1)(c) and 70 CRMW on migrant workers and their families .

- Right to enjoy benefits of scientific progress and its applications - art 15(1)(b) of ICESCR.

- Right to equality and non-discrimination - art 2(2) and art 3 of ICESCR; art 3 and 26- ICCPR .

- Benefits of science and technology shall not infringe on rights of individual or group, particularly privacy, human personality, physical and intellectual integrity- art 6 Declaration on the Use of Scientific and Technological Progress.

Where narrative promotes actions that contradict what is needed to globally bring an end to the pandemic:

- Principle of international cooperation and solidarity

- art 22 UDHR.

- art 55 and 56 UN Charter and ICESCR.

- Right to international solidarity in response to global health emergencies- art 2(b)- Draft RTI.

- Negotiations launched in 2021 for a ‘Global Pandemic Treaty’ to establish more specific obligations.

Hate Speech

Under Article 20 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, individuals of any nationality, race and or religion are protected from hatred that incites discrimination, hostility or violence. Some of the most dangerous disinformation campaigns emerge from known hate groups or frequent sources of hate speech. When hate speech paves the way for real-world harm against protected groups, international human rights law is violated.

A recent judgement from the European Court of Human Rights emphasised that to exempt a producer - i.e. a person who has taken the initiative of creating an electronic communication service for the exchange of opinions on predefined topics - “from all liability might facilitate or encourage abuse and misuse, including hate speech and calls to violence, but also manipulation, lies and disinformation” (see Sanchez v. France [GC] no. 45581/15, §185, 15 May 2023). The recent ruling concerned the very specific case of an individual, in his capacity as a politician, who was fined for failing to delete Islamophobic comments by third parties from his publicly accessible Facebook “wall” used for his election campaign. The third parties were also convicted.

Which human rights are impacted by hate speech?

- States must protect national, ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities - art 1 (1) 1992 Declaration .

- States parties must respect and ensure rights of individuals within its territory - art 2(1) ICCPR.

- Right to equality and non-discrimination ( art 2(2) and art 3 of ICESCR; art 3 and 26 of ICCPR).

- Right to self-determination and by future of this right, the right to freely pursue cultural development - art 1 (1) ICESCR.

- Right to take part in cultural life - art 15(1)(a) and conserve, develop and diffuse culture - art 15 (2) ICESCR.

- Ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities shall not be denied the right to enjoy their own culture, profess or practise their own religion, or use their own language

- art 27 ICCPR.

- art 30 CRC.

- States must prohibit and eliminate racial discrimination in all its forms and guarantee the right of everyone, without distinction as to race, colour, or national or ethnic origin, to equality before the law - art 5 of ICERD. Other civil rights such as:

- Right to nationality art 5 (d)(iii).

- Right to assembly and association art 5 (d)(ix).

- Right to opinion and expression art art 5 (d) (viii).

- Right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion - art 18(1) ICCPR:

- Right to privacy - art 17 ICCPR

- Right not to be subject to coercion that would impair freedom to have or to adopt religion or belief - art 18 (2) ICCPR.

- Right of parents and legal guardians to ensure the religious and moral education of their children in conformity with their own convictions - art 18 (4) ICCPR, art 13(3) ICESCR and art 14 (2) CRC.

Where advocating or inciting hate, discrimination and violence (not exhaustive):

- The inherent right to life which shall be protected by law (art 6 of ICCPR).

- Right to liberty and security of person (art 9 ICCPR).

- Requirement to protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse (art 19 CRC).

- Use of custom, tradition or religious considerations to avoid elimination of violence against women (art 4 DEVAW).

- Right to be free from torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment ( art 1 and art 4 of CAT).

Looking Forward

While these examples may seem outrageous, it is exactly this type of disinformation that garners the most attention and clicks. “Content Prioritisation” - the design and algorithmic methods that tech platforms use to promote or downrank content that appears in front of users - goes to the very heart of pluralism, diversity and the access to accurate, reliable information - a key aspect of freedom of expression and the foundation of a democratic society.

The algorithms used by tech companies for search, social and news feeds, are optimised for increasing advertising revenue. Algorithms promote highly engaging, often polarising content to users. The more people use a platform, the more advertising revenue is generated.

However, tech companies have recently shown a clear willingness and interest to better adhere to international human rights law. The foundational principles enshrined in the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights suggest that enterprises “should avoid infringing on the human rights of others and should address adverse human rights impacts with which they are involved.” As the United Nations has stated, businesses looking to prevent human rights violations “requires taking adequate measures for their prevention, mitigation and, where appropriate, remediation”. There is still ample space for companies to step up and exercise due diligence to comply with human rights law, where human rights refers to internationally recognized human rights

A variety of solutions have been proposed and piloted to confront the disinformation challenge, both from a legal and policy front as well as from a technology perspective. Some of these policy solutions, such as the Digital Services Act (DSA) within the EU, aim to protect users’ rights in online spaces, which are based upon existing international frameworks. Algorithms - unless regulated - often amplify the most polarising content. At its most extreme, adversarial narratives deliberately designed to promote real harm run directly counter to human rights for all.